Three young children peek their faces out of a makeshift tent. The oldest two are smiling, looking at the camera. Their tow-headed baby brother is looking down, his fingers holding something unidentifiable to his mouth. If you look carefully you can just make out the face of a fourth child inside the darkness in the tent. The children’s hair is tangled and their ill-fitting clothes are stained and filthy. The photo’s caption reads, “Lighthearted kids in Merrill FSA Camp, Klamath County, Oregon.”

Merrill, Oregon is a small town in Klamath County just five miles from the border with California. Today this rural area in south central Oregon has a population of just 845 residents and is best known for its yearly potato festival.

“People may say that progress and traffic move way too slow in Merrill,” reads the city’s website, “but just view it as an opportunity to take in the small town atmosphere and to revert back to when life was less demanding and less hurried.”

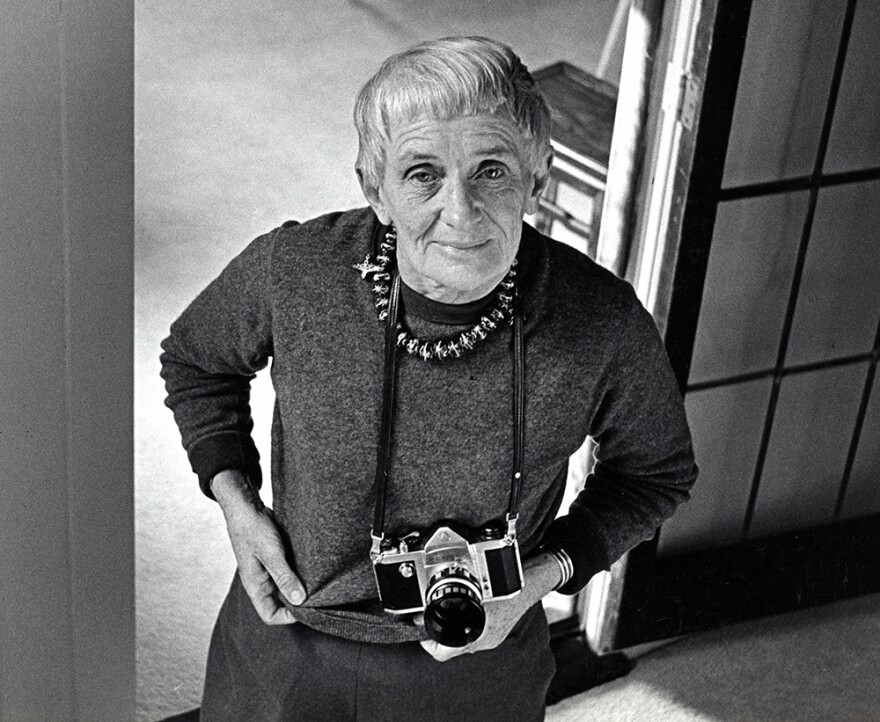

But when Dorothea Lange was photographing life in a makeshift government camp in Merrill in 1939 (when the “Lighthearted kids” photo was taken), life was very demanding. Our country was in the midst of the Great Depression, hundreds of thousands of Americans were heading to the West Coast to find work, and families on the move were suffering from lack of food, exposure to the elements, and extreme poverty. Small children, more vulnerable to malnutrition, infectious diseases, and even stress, suffered the most.

Even those well-versed in Dorothea Lange's photography usually aren't aware that Lange took over 800 documented photographs in JPR's listening area.

Dorothea Lange may be less well-known today that she was a generation ago, but most Americans are still familiar with her startling photographs. Her most famous, “Migrant Mother,” photographed at a pea pickers’ camp in Nipomo, California in 1936, has become an icon of the poverty and hardship suffered during the Great Depression. The photo is a close-up of a weather-beaten 32-year old mother—later identified as Florence Thompson—her brow furrowed with worry. Three children cling to her, two of them with their faces turned away, the other a chubby infant cradled in her lap. Migrant Mother, like “Lighthearted kids” and so many of Dorothea Lange’s photographs, are images with striking details and composition, more akin to Rembrandt paintings than to documentary photography.

But even those well-versed in Dorothea Lange’s photography usually aren’t aware that Lange took over 800 documented photographs in JPR’s listening area including in Jackson, Josephine, Klamath, Douglas, and Siskiyou, Shasta and Mendocino and Humboldt counties.

“The neglect of these Northwest photographs is a pity,” writes Linda Gordon, Ph.D., in a 2009 article published in Oregon Historical Quarterly. Though Gordon—a professor of History at New York University who considers Portland, Oregon her hometown and author of the comprehensive biography Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits—refers to Lange’s Oregon photos as “second best” and argues that they “do not match the stunning achievement of her Depression best,” Gordon concedes that some among them are masterpieces. As an adopted Oregonian with a keen interest in American history and people living on the margins, I find Lange’s Oregon and Northern California photographs as heart-stopping, heartbreaking, and culturally important as any of her better known work.

Photographing life in the region during the Depression

Dorothea Lange was sent to our region by the FSA—the Farm Security Administration—a program under the auspices of the Department of Agriculture that was implemented to fight against rural poverty. The FSA sent writers and photographers into rural areas where Americans were hardest hit by the Great Depression. The goal of the federal government was multifold, as Dyanna Taylor details in the documentary film, “Grab a Hunk of Lightening,” she made about her grandmother Dorothea Lange’s life.

The belief was that documenting the extreme poverty and devastating living conditions would help raise awareness of and sympathy for the families that were struggling the most. The program also created much-needed jobs for out-of-work writers and photographers.

When Lange came to Oregon, the state was mostly agricultural—over three quarters of the population depended on farming and forestry. While some energetic entrepreneurs—notably brothers Harry and David Rosenberg who inherited their father’s 240 acres of pear plantations in the Rogue River Valley—were able to utilize the inexpensive land in Southern Oregon by growing and selling specialty products to wealthy customers back East, for many life was difficult. Oregon was mostly rural expanses and its population was less than one million, four times smaller than it is today. Nearly a third of the farms in Oregon had fewer than twenty acres. Despite fertile soil and mild weather with temperatures conducive to growing a variety of crops, small family farmers lived modestly and worked hard, making less than $800 a year. When the economy took a downturn in the Great Depression, family farmers in Oregon were hit hard.

People who lived through the Great Depression remembered “Black Tuesday,” as if it had happened yesterday. That stock market crash of October 29, 1929 catapulted the country into the most severe economic downturn it had ever experienced. Americans started to panic as the banks failed. I asked my grandmother about the day the bottom dropped off the American stock market when I was in sixth grade and we had been assigned John Steinbeck’s 1939 The Grapes of Wrath, a novel as iconic to that time period as Dorothea Lange’s photography (Lange and Steinbeck visited many of the same migrant camps and the San Francisco News used seven of her photographs to illustrate his articles).

Even fifty years later, she remembered with sadness how unemployment rates soared, she and her friends felt hopeless, and the once so promising future—after ten years of economic prosperity—started looking very bleak. In 1929, however, President Herbert Hoover described the economic downturn as just a “passing incident in our national lives.” Hoover believed that the economic crisis would resolve on its own and insisted that it was not the federal government’s responsibility to try to fix things.

By 1932, things had gone from bad to worse and a devastating percentage of able-bodied American men were unable to find employment. By 1934 the Great Plains were experiencing severe droughts and dust storms. Farmers, who inadvertently created an environmental disaster by clear-cutting enormous swaths of forest to plant crops, reported insect infestations and crop failures. Inclement weather and huge wildfires made the land even less yielding. Recurrent windstorms (“black blizzards”) kicked up huge clouds of dust, choking cattle, killing livestock, and destroying crops. One Nebraska farmer remarked with disgust that the only thing he could raise on his farm was weeds and grasshoppers. These poor conditions drove an estimated 60 percent of families out of the region that became known as the Dust Bowl. These “Oakies” (though they often weren’t from Oklahoma) headed west in search of fertile soil and a better life. By 1940 well over two million people had left the Midwest, nearly 10 percent of them taking up permanent residence in California and at least 200,000 of them trying their luck in Oregon, according to historian Linda Gordon.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office as president in March of 1933, he implemented a dramatically different government than Hoover. Roosevelt felt it was the responsibility of the federal government to stabilize the economy, provide jobs, and offer relief to the people who were suffering. Over his two terms in office, Roosevelt created a series of projects and programs, referred to collectively as the New Deal, aimed at restoring prosperity in America. The Farm Security Administration was one of those programs and Dorothea Lange was one of the photographers who helped make it successful.

Lange took photographs in Siskiyou County, California and Oregon in the summer and fall of 1939. She traveled along the winding Highway 99 between Medford and Grants Pass, Oregon and Olympia, Washington—which was being used both by loggers and by migrating families—as well as along Highway 30 to Boise, Idaho.

She documented migrant families on the road, life in temporary FSA tent camps, as well as people in small towns going about their business: a hop picker with two restless children at the paymaster’s window of a company-owned store in Josephine County, near Grants Pass (the accompanying caption explains that she bought one pound of bologna sausage, a pack of cigarettes and a “mother’s cake” with the forty-two cents she had earned that morning); a farm boy in a broad-brimmed straw hat and ripped dungarees reading the news in front of the latest magazines on sale at a corner store in Medford; a well-heeled new arrival to Oregon (“Mrs. Botner”) examining the rhubarb in a box in her cellar storage in Malheur County surrounded by the 800 cans of vegetables she put aside for the winter.

During this time it was common to see families, their possessions piled high in their vehicles, stuck on the side of the road. Some were there for a few hours but other families, their vehicles broken beyond repair or without money for gas, would end up living on the side of the road for weeks.

In another photo of children smiling taken near Merrill, Oregon in September of 1939, two boys wearing overalls and plaid shirts peer down from the back of a flat-bed truck that is covered over with canvas, reminiscent of the horse-drawn wagons from pioneer days.

8b34858a Just arrived from Kansas. On highway going to potato harvest. 1939 Sept. Near Merrill, Klamath County, Oregon.

8b34858a Just arrived from Kansas. On highway going to potato harvest. 1939 Sept. Near Merrill, Klamath County, Oregon.

Credit Call Number: (Library of Congress) LC-USF34-021001-E

The family’s bedsprings are fastened to the side of the truck. The older boy leans far out, ready for action; his little brother looking impishly at the camera. The caption reads, “Just arrived from Kansas. On highway going to potato harvest,” and the image gives the impression that the children are gleefully anticipating their upcoming adventure. But a wider-angled photo in the same series paints a more subdued picture: the father kneeling by the back wheel, removing the nuts with a tire iron as he changes a seriously blown-out tire.

“A demanding, difficult, charismatic person”

Though she spent most of her adult life living on the West Coast, Dorothea was actually born in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1895. Her father, Heinrich Nutzhorn was a lawyer, her mother Johanna a homemaker. Her parents valued education and the arts and the family was comfortably middle class, but by most accounts Dorothea’s childhood was not easy. At seven she contracted polio, which permanently deformed her right foot and left her walking with a limp. When her father left her mother five years later, Dorothea Nutzhorn stopped using his last name and took her mother’s maiden name, Lange, instead. With no means of support after Nutzhorn abandoned the family, Dorothea’s mother took her and her brother Martin to live with her mother, who worked as a seamstress.

“I know that her mother and grandmother both were very hard on her and made her walk all the time, as best she could,” Lange’s cinematographer Dyanna Taylor remembers, when I interview her on Skype about her remarkable grandmother. “Her limp was something they wanted to hide,” she laughs sadly. “I think they were afraid she wouldn’t be marriageable.”

Dyanna Taylor is the granddaughter of Paul Taylor, Dorothea Lange’s second husband. Her film, “Grab a Hunk of Lightning,” which premiered on PBS in 2014, paints Lange as a feisty, energetic, adventurous young woman who wasn’t afraid to skip school to walk the streets of New York’s Bowery, knew with absolute clarity that she wanted to be a photographer even before she had ever held a camera, and was keenly interested from a very early age in documenting the truth about people’s lives.

In her early twenties Dorothea Lange planned to travel the world with her best friend Florence (“Fronsie”) Ahlmstrom. But the day they landed by steamer in San Francisco they got pickpocketed, losing all their money for the trip. Lange had to go to work, first as a photo finisher and later opening her own studio, which catered to San Francisco’s wealthy families. But she soon became dissatisfied with boutique photography, turning instead to the unemployed men queuing in the bread lines she saw outside her window. In 1920 she married painter Maynard Dixon, who was 20 years her senior, in 1920. They had two sons together, Daniel and John. Raising a family, which included Dixon’s daughter Constance by a previous marriage, being an attentive artist’s wife, and becoming a master photographer proved tremendously challenging, and for a time her sons were sent to live with foster families.

In 1935, still married to Dixon, Lange met Taylor’s grandfather. Paul Taylor was a progressive economist with a keen interest in environmentalism and in helping the poor. Dyanna describes her grandfather as the second of Lange’s great muses (the other being her first husband), a man deeply in love with Lange, supportive of her work, and mindful of the bigger political and sociological implications of her photography. Taylor had three children from his first marriage. Lange and Taylor both divorced their spouses in order to marry each other.

Talking to her granddaughter made me wonder if perhaps one of the reasons Lange so effectively captured pain and hardship in so many of her photographs was because her life was also marked by emotional and physical pain.

“My grandmother was a demanding, difficult, charismatic person,” Taylor says honestly.

She was also often in physical pain, plagued with fatigue and muscle weakness from having survived polio (a condition called post-polio syndrome) and with symptoms from undiagnosed esophageal cancer, which made it uncomfortable for her to eat, especially in the last year of her life.

But it was precisely because Lange was so unassuming and unintimidating with a camera in her hands that she was able to get such candid shots.

“She would show her camera to the kids, limp around, talk to them. She was looking down into a Graflex or a Rolleiflex, bent over, and she was tiny,” Dyanna Taylor explains. “Because she’s lower than they are, she’s ennobling her subjects as well, which is part of the beauty of her photographs. A lack of intimidation, a lack of having a camera in their face. That’s part of what makes her pictures so honest.”

Honest. Beautiful. Painful. Joyous. And all totally addictive. Whether it is a picture of the three crooked steps leading up to an old Catholic church on the edge of potato town in Klamath County, Oregon or the calves of a woman wearing stockings whose rips have been carefully sewn up time and again in San Francisco, California, you can’t stop looking at the images of this master photographer.

Dorothea Lange died in 1965 at the age of 70, leaving behind a body of work that is as timeless as it is historically important.

_________________________________________________________________________

For more on Dorothea Lange’s FSA photographs visit http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ (search Dorothea Lange)

The photographs in the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection form an extensive pictorial record of American life between 1935 and 1944. This U.S. government photography project was headed for most of its existence by Roy E. Stryker, who guided the effort in a succession of government agencies: the Resettlement Administration (1935–1937), the Farm Security Administration (1937–1942), and the Office of War Information (1942–1944). The collection also includes photographs acquired from other governmental and non-governmental sources, including the News Bureau at the Offices of Emergency Management (OEM), various branches of the military, and industrial corporations. In total, the black-and-white portion of the collection consists of about 175,000 black-and-white film negatives.

For a more detailed look at Dorothea’s work by county visit http://photogrammar.yale.edu/map/

Jennifer Margulis, Ph.D., is an award-winning journalist, book author, and Fulbright grantee. A regular contributor to Jefferson Public Radio, she has published articles in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and on the cover of Smithsonian magazine. Her most recent book, co-authored with Paul Thomas, is The Vaccine-Friendly Plan: Dr. Paul’s Safe and Effective Approach to Immunity and Health, From Pregnancy Through Your Child’s Teen Years (Ballantine 2016). Read more about her at www.jennifermargulis.net.