Of the more than 45,000 babies born in Oregon each year, nearly a third are delivered by Cesarean section. Yet studies show that surgical birth is riskier for the mother, and not as healthy for the baby, as vaginal birth.

Women who give birth out of hospital are much less likely to have C-sections. But low-income Oregonians and the midwives who care for them say that a state agency is unfairly blocking women from even trying for a vaginal birth.

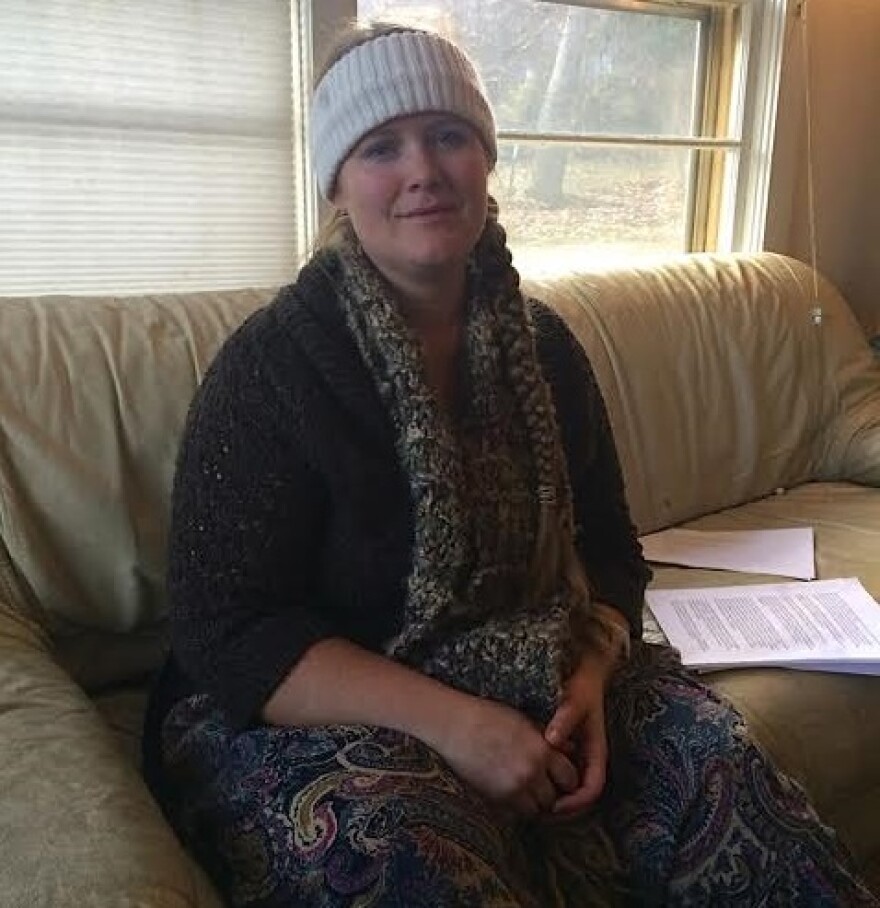

Laura Blevins should be on top of the world. She’s 29, recently graduated from medical school in Portland, and has her first job in private practice. She now lives in Klamath Falls and is expecting her second child.

“I have one four year old,” she says. “And then I actually had four miscarriages while going through med school, and I’m currently 24 weeks pregnant with my little girl.”

But Blevins’s first birth didn’t go the way she planned. After a long and difficult labor, the doctor suggested vacuum suction.

“I just felt like he was stuck and trying to vacuum birth him out would have caused both of us more harm, and when he came out he had a big lump on the side of his head.”

So Blevins opted for a cesarean. She says she was treated respectfully by the doctor and the hospital staff.

“It was the best case scenario that it could be for the situation,” Blevins says. “But it’s definitely not what I planned and it’s not what I want to do this time.”

This time Blevins is planning for a VBAC: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean. She says she’s thoroughly researched her options and that she wants to have a vaginal birth because she’s concluded, as a doctor, that a VBAC is the best and safest option.

Andy Kuzmitz is a family physician in private practice in Ashland. He says babies born by Cesarean are at a higher risk for a host of medical problems, especially digestive disorders.

“It’s not unusual for babies born by C-section to have trouble with their GI system for their first few months or even the first couple years of their life.”

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, VBAC is also better for the mother, decreasing the risk of hemorrhage and infection and shortening a woman’s recovery time.

But despite all of the advantages of vaginal birth over cesarean, Laura Blevins says she’s being blocked from even trying for a VBAC. Blevins says she can’t find a doctor who will even allow her to attempt a vaginal birth.

“There are no providers in Klamath Falls who will do a hospital VBAC."

So to have a vaginal birth, Blevins has to have an out of hospital birth; either at an independent birth center or at home, cared for by state-licensed midwives.

She’s paying off enormous medical school debt and for now she gets her insurance through the Oregon Health Plan, which provides insurance to low-income Oregonians. Though the Plan covers out of hospital birth for some women, the Oregon Health Authority has new guidelines that no longer cover any out-of-hospital births if the woman has had a prior Cesarean for any previous pregnancy.

OHA officials refused repeated requests for an interview. In a written response, they explained they’re now refusing out of hospital VBACs because an internal review board found that “women who have had previous C-sections cannot be determined low-risk.”

But Hermine Hayes-Klein, a Portland lawyer and international expert on childbirth, says that out of hospital VBAC is a safe and reasonable option for many women, one that’s often less risky than repeat C-section.

“It doesn’t make economic sense for the Oregon Health Plan to refuse to cover a low-cost low-risk birth and instead drive women into expensive surgeries that pose a genuine risk.”

Hayes-Klein says the Oregon Health Authority’s new, more restrictive guidelines are making it impossible for low-income women to have vaginal births after Cesarean.

“What these women are left with is only the choice for planned repeat surgery,” she says. “Of course [that’s] much more expensive to the OHP than a vaginal birth with a midwife would be.”

Laura Blevins submitted all the paperwork the state required, which included going to an obstetrician for a consultation because of her previous miscarriages.

But for three months, she and her midwife were told that her application for insurance coverage was “pending.” We reached her when she was 32 weeks pregnant. She told us she was feeling anxious and stressed out:

“I’ve still be hanging on by a thread,” she says. “I keep checking with OHP.”

A few weeks before her due date, Blevins finally heard back from the Oregon Health Authority in writing. Her application for insurance for a vaginal birth was denied.

Blevins still plans to deliver her baby girl at a birth center because she feels a vaginal birth is the safest, healthiest choice.

And after the baby is born, she says, she’s planning to sue the state.