The thought of reviewing the range of non-professional theatre in the Rogue Valley, and pondering the question of what community theatre might be, has always intrigued me. Bear with me as I explore the rich history and bright future of community theatre, nestled right here amidst the peaks and valleys of the Siskiyou mountains.

Back in Bavaria, in the seventeenth century, the citizens of the village of Oberammergau made a vow that, if the village was spared from the effects of the bubonic plague, they would perform a Passion Play every ten years afterwards, until the end of time. Generations of villagers have kept that promise to God, and the play has been performed in every year ending in zero since 1640, with the single exception of 1940 when World War II intervened. There has been some updating of the script and of the musical score which accompanies the play, but the work is essentially the same, and it is performed in the summer in the open-air in a production which involves the whole village.

The Oberammergau Pas- sion Play attracts an audience of thousands from all over the world, and the economy of the village relies heavily on the tourists who come there; it represents one very particular model of “community theatre”. Although it is not theatre for the community (it is theatre for God), it is certainly theatre performed by the community — classes at the local school are arranged so that the children can be on stage for the large-scale scenes at the beginning and end of the play, and I can vouch for the fact that there is a real frisson when you realize that your lunch has just been served to you by Judas Iscariot, or that you have just bought a postcard from Mary Magdalene.

It might seem strange that that there is any non-professional, community theatre at all in the Rogue Valley when there are such well-established professional companies. The Oregon Cabaret Theatre in Ashland has been presenting professional shows in its converted pink church since 1986, there has been professional theatre at the Craterian Theatre in Medford since the 1990s, and the Valley is the home of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, one of the largest repertory theatre companies in the world. So what does community theatre mean in this region? What is it doing and what are its challenges?

Perhaps it might be best to start by questioning that distinction between full-time professional theatre and its community counterpart. People in the Rogue Valley are probably accustomed to seeing in Sneak Preview the names of people we know who work during the week and perform in the evenings and at weekends at the Camelot Theatre in Talent, but there is no hard and fast division between professional and amateur theatre in the region. The Cabaret Theatre auditions performers from all over the country, but, if you catch a show there, you might just see local artistes in the cast, like John Leistner, Tamara Marston, John Stadelman and Suzanne Seiber; you know they have other jobs, and that they are not full-time actors and musicians, but they are certainly part of professional theatre.

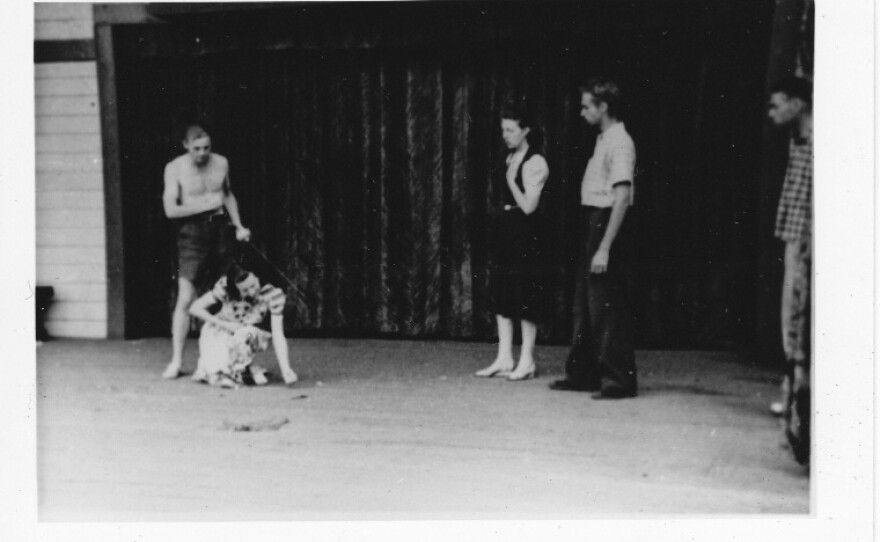

What is perhaps easier to forget is that OSF did not start as a professional theatre company. When Angus Bowmer produced Ashland’s inaugural ”First Annual Shakespeare Festival” in 1935, he was teaching at the Southern Oregon State Normal School, and he continued to teach there and at its successor institution (Southern Oregon College) throughout his time as producing director at OSF. Bowmer took the leading male roles in both of the plays staged in 1935, casting prominent members of the community in prominent supporting parts. I am excited that audio and film-clips of early OSF productions have been made available on YouTube, so that it is now possible to hear Angus Bowmer in performance. Even now, although local actors do not take the leading roles in OSF productions, there are still separate auditions for local actors, some of whom, like David Dials, have played for a full season at the Festival, as well as taking part in productions at the Camelot. And, of course, OSF continues to look to local children to play the roles of the younger members of the cast. However, almost all of the current OSF company are full-time actors, sometimes supplementing their income by narrating audio books or by giving talks to groups coming in to see the plays; as far as I know, none have followed in the footsteps of Bill Patton and Richard Hay who, when they came to Ashland, sold fireworks to fund their stay.

Angus Bowmer was a living link between Ashland’s Festival and its higher education institution, and Southern Oregon University is, in itself, a center for community theatre, albeit a community of a somewhat closed kind. The University’s Theatre Department stages plays of high quality, and its alumni include Ty Burrell and Rex Young.

In his novel Beautiful Ruins, Jess Walter writes of “the community-theatre fund-raising trick: cast as many cute kids as you can and watch their … parents … buy up all the tickets, then use the proceeds to pay for the arty stuff.”

I have not seen this as an operating principle in this region (although the technique of name-dropping is one which also applies to the press, and I am aware of the running tally of names in this piece). Its high schools serve the community through their theatrical productions, and their audiences are often boosted by parents, grandparent, uncles and aunts all eager to see their young relatives display their talents, but their work is by no means confined to the cute and the populist: witness Ashland High School’s ambitious production of Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories in 2011.

However, what, perhaps, distinguishes University and High School productions from other kinds of community theatre is the simple issue of budget. I have no doubt that theatre in universities and schools work within financial constraints, but I am equally sure that they are not as dependent on ticket receipts as are community theatres outside of the world of education. As I keep saying to my own students, theatre is an expensive process. If I write a novel or a poem, I need inspiration and some paper, and that is it. I can test my work out by simply abusing the goodwill of my friends and sending them drafts to read. The maximum loss which I can sustain is my time, my paper and my list of friends. If I embark upon the project of writing a play, I can lose all of that and a whole lot more.

Novels require readers, but the novelist can have no notion of how the readers respond in that privacy of their own reading time. Plays require actors, directors, set-designers, lighting designers, sound designers. All those who have ever attempted to write for the stage will know that they are merely one part of a complex and expensive jigsaw: what they imagine they have written may be totally refashioned by the director, and, when the cast gets on-stage, well….

If community theatre is performing any kind of service, it surely needs to be serving local writers and directors as well as local actors. And there’s the rub. I live in hopes that a local group will want to stage Oliver!, because I have always wanted to play Fagin, and I am ready, willing and able. This is not an impossible dream, because Oliver! is a proven show with a substantial track-record, a record which substantially reduces the risk for any group planning this as part of a forthcoming season. If, however, I am a playwright seeking an opportunity to see my work staged live in a theatre, my dream looks much less likely to be realized. To even get my play read, I need actors, a director, and a venue, and that reading may not be enough to reveal flaws in the writing. For example, at the beginning of Act Three of King Lear, Shakespeare has Kent and a Gentleman agreeing that whoever finds the King will alert the other: this never happens. In the previous scene of that play, Shakespeare has Gloucester present for hundreds of lines with nothing to say: I spent months in that role in 2011 trying to work out what to do – I failed to find an answer.

There are groups in the region which encourage and foster new work. One of these is The Ashland New Plays Festival which has taken on this role since 1993, and, more recently, the Atelier has presented a monthly series of unrehearsed, undirected table readings by local actors; this has now developed into directed and rehearsed staged readings by the company.

These projects go a long way towards reducing the risk of full staging, whilst still giving the writers a sense of how their work might sound, but mounting a full-scale production, especially a production of a new play, remains a daunting task for a community theatre. In the relatively brief time I have lived in the valley, I have seen two local groups close, one of which closed within the past year. Play readings do not rely on revenue from an audience; full-scale productions depend absolutely on finding and pleasing that audience. As I write, I note that there is at least one new company taking the stage in Ashland, and I wish Theatre Convivio all the very best in its endeavors.

There are two groups in Medford which are currently taking up the challenge of staging full-scale productions. One is Next Stage Repertory which has formed a partnership with the Craterian Theatre and is regularly performing there. The other is The Randall Theatre which, in my view, is going a long way to redefine just what community theatre might mean.

The Randall, now in its third season, operates on a shoe-string budget out of an old warehouse in downtown Medford, which used to be a storage house for various companies in the valley, including West Coast Paper. The advantage of its location is that there is no shortage of space, so one play can be in rehearsal while another is being staged, and there is plenty of room for storage, and for the mounting of an elaborate Halloween show (now an annual event). The disadvantage is that this is not a purpose-built theatre, and so sometimes things go awry. OSF, its illustrious near-neighbor, had a problem with the roof-beam of one of its theatres in 2011, the Randall had a leak in its warehouse in February 2012, and one production had to be transferred to North Medford High School. This kind of response to an emergency can be effected more easily with an operation which has already been stripped to the bone, and it allowed the Randall to further one aspect of its mission – to work with the local community, including schools (such as McLoughlin Middle) and the Rogue Valley YMCA.

Robin Downward, the theatre’s Managing Artistic Director, is very aware of the fact that there are fewer and fewer opportunities for young people to become involved in theatre. Pressures on time are forcing drama out of the curriculum altogether in some schools, and there are almost no opportunities for students beyond high-school level to engage in theatre, except for degree-level programs. He is, therefore, trying to meet this need by taking drama into the community by way of his team of volunteer teachers. It is his hope that this will go beyond the summer schools offered by other theatre companies in the area, and become an ongoing, year-round project.

The Randall has an ambitious program of productions, including musicals, established drama and new plays. In May 2012 I saw the first production of Just Cause by local playwright Greg Younger. The theatre strives to be welcoming and open to its potential audience. You are unlikely to see fur coats and tuxedos there, and the theatre operates a ticket policy of “Pay what you want”, with the proviso that, if you liked the show, you can always pay a little more on the way out. In a way, this policy parallels one way in which OSF tries to stay in touch with its own local community by offering them special ticket prices, especially at the beginning and end of its season. I have to say, also, that I am continually impressed at the willingness of OSF actors to talk about their work in chance encounters with strangers (OK – with me …): this is not something I have found to be true of actors in the UK. One British actor I exempt from that charge is a now-famous film actor who has always been willing to talk to me about his work – but that could be because he knows I know his mother and he lives in more fear of her than of any motion-picture academy jury.

Robin Downward, who named the theatre in honor of his late brother, has a vision, and he articulates that vision in these terms:

“I want people coming to the theater to experience that ‘Off Broadway’ feel in Medford — excellent work but without the glitz and glamour — theatre with a few rough edges so that it still feels like theatre, not film. I never wish to hide that we are in a converted warehouse. As we look to enhance its look over time, we could never hide the fact that the building is not a traditional theatre and I would never want to. If there has been a draw back to our home, it’s that the perception of what theatre is in the valley to many patrons is that theatre happens, or should happen only inside large, decorated, updated beautiful live theatre venues.”

There is a danger in theatre, as in many areas of life, of confusing style with substance. “Theatre” is not the same as “a theatre”, the craft is not synonymous with a building, any more than worship is synonymous with a church or a temple. Theatre can take place in the open-air (as it did at the very beginning of the history of OSF), in a private house, or in the top-floor of a pub; the splendor of the theatre building might indeed be misleading, if it masks the poor quality of the performance which lies inside.

Robin is absolutely right in emphasizing the difference between theatre and cinema. A film is the same at every screening, nothing changes and the actors neither grow older nor do they respond to the reactions of the audience: the film goes on whether or not the audience is present. Every theatrical performance is different, and sometimes mistakes are made, and the cast must work quickly to get the show back on track. That never happens in the cinema – if an actor falls over on the cinema screen, it is because the director intends that to happen: if an actor falls over on the stage of the theatre, it may not be intentional at all. Once the film has been completed, it cannot be improved upon (except in a few instances of “Director’s Cuts”): it is over. A play on stage is never done, and performances can always change. There is a dreadful irony in the fact that what actors most wish for is steady work, but a long run in a successful show can become as tedious as working on an assembly line. I have a friend who spent five years in one particular play, and who felt that about 75% of that time was a sort of living death.

In 1935, Angus Bowmer had a vision, and he can only have dreamed that that vision would develop from presenting two Shakespeare plays under the stars to the current Festival which stretches over ten months in three theatres. I had the privilege of teaching a Shakespeare class at SOU last year, and of experiencing extraordinary generosity not only from the staff of OSF, but also from the kind gentleman who gave free tickets to one of my students who might otherwise have found it difficult to go to an OSF performance. That student had never seen professional theatre before, and immediately fell under its spell, but the spell is there whether the theatre is professional or amateur, Festival or community. And that is why community theatre is here in the Rogue Valley, because the Valley draws to it people who are passionate about theatre, and who want to participate in it – people like me.

Geoff Ridden is a volunteer host on the Classics and News Service of JPR, and a regular contributor to the “Recordings” column of the Jefferson Monthly. He has been a permanent resident of Ashland since 2008. He is ready to play Fagin at a moment’s notice…

___________________________________________________________

Ashland Contemporary Theatre

No discussion of local theatre would be complete without mentioning one of the Rogue Valley’s iconic theater groups, the Ashland Contemporary Theatre (formerly known as Ashland Community Theatre, or ACT), which has kept local audiences entertained for over 23 years. The company performs regularly at the Ashland Community Center and winery venues around the county, bringing "new work, great writing and fresh ideas" to local audiences.

Their mission is to present works of literary merit, particularly from the last forty years, and showcase the finest writing created by the Rogue Valley's many playwrights. Since 2007, ACT has premiered over 110 new plays by nearly forty local authors, through its "Paschal Readings," "Quarter Moon," and "Moonlighting" series devoted to short plays. The most recent, "Moonlighting 2013" was produced last June and July at the Community Center and Grizzly Peak Winery, with the 60 seat winery performances selling out to standing room only.

Founded in 1991 by actors and directors, several of whom were peripherally involved with OSF, ACT is dedicated to being a truly avocational company, drawing on the talents of artists and technicians from around the Valley. The group prides itself on making theater a community participation event; part of its mission being to provide experience and informal training to budding theater enthusiasts.

Although ACT has produced both one-acts and full length plays in every year since its inception, it was in 2010, when the company altered its name to "Contemporary" and Jeannine Grizzard became Artistic Director that production output increased dramatically. Between 2010 and 2013 alone, there were twelve full productions and eight readings.

ACT mounted the premiere of Pompadour, a one woman play featuring Grizzard and written by well-known local playwright and Jefferson Monthly contributor, Molly Tinsley, which was widely praised and sold out the whole of its run. Previously, End Days and Breaking the Code met with particular audience and critical acclaim.

Following Greetings! last Christmas, director Evalyn Hansen surprised audiences in March with edgy comedy in Durang's 7 Shorts. The community can look forward to another production by Ashland Contemporary Theatre in mid-June. Dates to be announced soon. More at www.ashlandcontemporarytheatre.org

Joe Suste, Ruth Wire, & Jeannine Grizzard